In this blog article, we delve into two essential software design principles: Command and Query Separation (CQS) and Command-Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS).

An example of separating commands and queries: the left ATM allows you to deposit money (command), and the right one shows your current balance (query).

Command and Query Separation Principle (CQS) Link to heading

CQS was introduced by Bertrand Meyer in 1994. As the creator of the programming language Eiffel, he also pioneered the concept of “Design by Contract” (DbC), which I explored in greater detail in a recent blog post – See: Here.

CQS essentially advises separating query operations from command operations within your methods. But what exactly do we mean by a query or a command?

Query Link to heading

A query is any method that retrieves information without changing the state of the system. A query is asking a question and returns the answer.

For instance, a method that fetches data from a database and returns it to the caller qualifies as a query. It merely reads the data without modifying the application’s state.

Command Link to heading

A command represents an operation that alters the application’s state. Unlike queries, commands do not return values.

For example, a method that inserts an object into a database performs a write operation, thereby changing the state of the system. Such a method completes its task without returning a result.

CQS violation Link to heading

The principle’s goal is to ensure a clear separation between methods that change the application’s state and those that do not.

-

If a method performs a write operation on the database (changing the state) while returning a value, it breaks the CQS principle.

-

Similarly, if a method fetches data from a database but simultaneously modifies the state of the system, it also violates CQS.

Combining commands and queries in one method is strictly prohibited! This principle is often summarized by a well-known quote:

Asking a question should not change the answer! — Bertrand Meyer

If these rules are adhered to, the following correlation naturally arises:

A query will return the same result each time it is executed, unless a command has been performed in the meantime.

CQS and REST Endpoints Link to heading

This principle is equally relevant when designing REST endpoints. Ensure that each endpoint either executes a query operation or a command operation, but not both at once. In the context of CRUD functionality, CREATE, UPDATE, and DELETE are command operations, whereas READ is a query operation.

Let’s explore the five HTTP methods in REST:

- GET (Requests a resource from the server)

- POST (Creates a new resource on the server)

- PUT (Modifies the entire resource on the server)

- DELETE (Deletes a resource from the server)

- PATCH (Modifies only parts of the resource on the server)

Only the GET method aligns with a query operation. Methods like POST, PUT, DELETE, and PATCH are command operations, as they modify the application’s state.

To adhere to the CQS principle with REST endpoints, an endpoint must not both return data and modify the state. If this occurs, the functionality should be split into two separate endpoints.

Advantages of CQS Link to heading

-

Makes it easier to reason about your code: You develop an intuitive sense of whether a function alters the state. This allows you to quickly identify methods that are safe to call when you want to avoid changing the application’s state.

-

Isolation of mutations

-

Simpler code: Methods are reduced in size, easier to understand, and more focused on their specific task.

-

Separation of concerns: Breaking down complex code into simpler, isolated tasks.

-

Easier testing: Functions that focus on a single task are simpler to test.

-

Clear API design: Using a naming convention to define which methods are queries and which are commands is a useful practice. I believe it’s essential to apply this principle when designing REST endpoints.

-

Not adhering to CQS can be risky: Imagine a scenario where a GET endpoint is called to perform a read operation, but the application’s state is modified in the process. The caller might not be aware of this change, and their intention was probably not to alter the state by making this call.

Exceptions – When is it acceptable to violate the principle? Link to heading

There are certain edge cases where violating this principle might be justified.

Martin Fowler discusses an interesting example in his Online-Blog, where he explains that the pop operation on a stack violates the principle. This is because it both retrieves an item from the stack and modifies its content, mixing a query and a command. Martin Fowler says: “So I prefer to follow this principle when I can, but I’m prepared to break it to get my pop.”.

Recently, I encountered a similar situation at work. I was tasked with creating a new endpoint to save an object to the database, so I implemented a typical POST endpoint. As is standard, the resource to be saved is sent in the request body, and the endpoint inserts it into the database. Naturally, the entity in the database has an auto-generated ID as its primary key. All seemed fine up to this point.

However, shortly afterward, a frontend developer from my team approached me. He explained that the frontend needed the ID of the newly created object, as it would later use it to request the object through the GetOneObjectByID endpoint. He suggested that the POST endpoint (which saves the new object to the database) could also return the ID of the new object in the response body — or even better, the entire object. This would allow the frontend to process it immediately. Upon researching online, I learned that this is actually quite a common practice.

I was not at all convinced by the suggestion to mix command and query operations in the POST endpoint, as it directly violates the CQS principle. One potential solution I considered was creating a separate endpoint that returns the last object saved by the user. Yet, even this solution has its flaws, as it would introduce unnecessary complexity by requiring the program to check the create_date of the object in the database. Moreover, this additional endpoint wouldn’t guarantee the return of the exact object, as it always fetches the most recent one. What if the user saves more objects? What if concurrency becomes an issue? How does the application behave under high load? This could introduce even more problems than the frontend developer’s initial suggestion.

Another question is how endpoints should generally handle exceptions and errors. If a command operation throws an exception, should the endpoint return an error message in the response? This would also violate the principle. However, the frontend needs to notify the user when something goes wrong and, crucially, explain WHAT exactly went wrong. Without an error message in the response, this would be impossible.

As you can see, there are situations where following the CQS principle can be questioned. Ultimately, each developer must make an informed decision on whether to apply or violate the principle in each case. Software design principles are guidelines, not rigid rules, meant to improve code. However, these principles can sometimes conflict with each other. The key is to think carefully and make a conscious decision. Discussions with like-minded developers can be a valuable part of this process.

Command-Query-Responsibility-Segregation (CQRS) Link to heading

As previously explained, CQS applies to functions or methods, while CQRS, the “big brother” of CQS, operates at the architectural level of applications. It treats reading and writing as entirely separate subsystems. CQRS was first introduced by Greg Young in 2010.

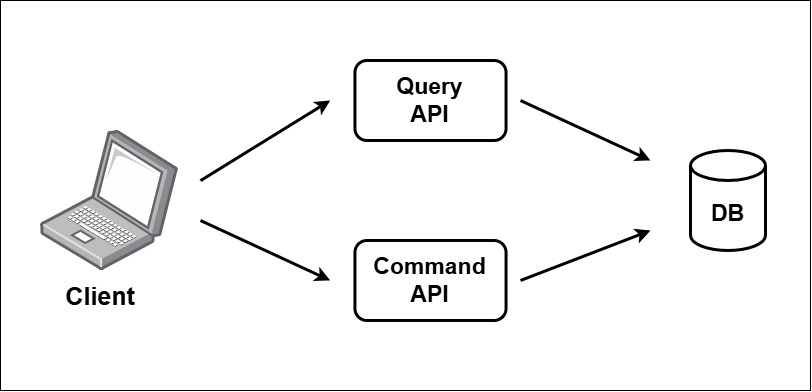

Udi Dahan analyzes two key CQRS patterns in his presentation CQRS pitfalls and patterns: the “Standard CQRS Pattern” and the “Eventually Consistent CQRS Pattern”. As illustrated in the following image, an application that follows the “Standard CQRS Pattern” utilizes two distinct APIs: one for query operations and one for command operations. The query API handles reading data from the database, while the command API is responsible for writing data. It’s important to note that both APIs access the same database.

The Standard CQRS Pattern (Source: Udi Dahan).

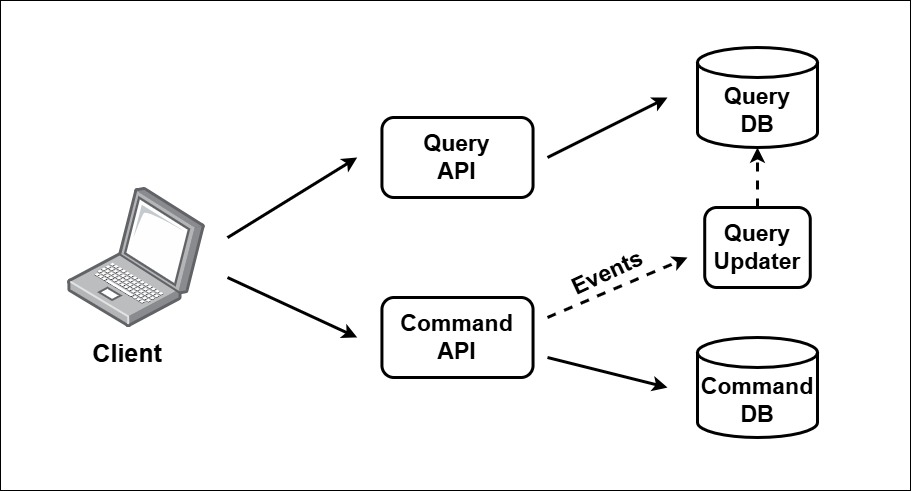

You could take this approach even further by assigning a separate database to each API. Why would you do that? Because this allows you to tailor the query data model for fast read operations, while optimizing the command data model for write operations. Both sides can then perform their tasks more efficiently, as each is focused on a single purpose. However, this requires a mechanism to keep both databases in sync. When the command database is updated, the query database must reflect those changes as well. The following image illustrates the “Eventually Consistent CQRS Pattern”.

The Eventually Consistent CQRS Pattern (Source: Udi Dahan).

In this architecture, the Query-API interacts with the Query-DB, and the Command-API interacts with the Command-DB. When the Command-API modifies data, an event is sent to a “Query Updater,” which propagates the changes to the Query-DB. While this synchronization is typically asynchronous, it can introduce challenges such as delays. For example, users might experience inconsistencies when querying data they’ve just updated. These issues are especially problematic under high loads (e.g., 10,000 commands per second) or when the Query Updater becomes a bottleneck. Therefore, in CRUD systems, the “Eventually Consistent CQRS Pattern” should be avoided if the Query Updater cannot maintain pace.

It is crucial to emphasize that CQRS is an architectural style, not a universal “best practice.” Like any tool, it should be employed only when it is appropriate to the specific problem at hand. The decision to use CQRS ultimately rests with the software architect, who must carefully evaluate its relevance and benefits.

Reference Link to heading

Videos Link to heading

-

Video from Christopher Okhravi: Command Query Separation (CQS) | Code Walks 025, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zXJORh8K4Bw, Last Access: 21st November 2024.

-

Video from Bran van der Meer: How to CQS: splitting the Read from the Write, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8-1fclzVm8w, Last Access: 21st November 2024.

Conference Link to heading

- Presentation from Udi Dahan: CQRS pitfalls and patterns, NDC Conference in Oslo 22-26 May 2023, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lw04HRF8ies, Last Access: 21st November 2024.

Websites Link to heading

-

Blog-Article from Martin Fowler: Command Query Separation, URL: https://martinfowler.com/bliki/CommandQuerySeparation.html, Last Access: 21st November 2024.

-

Wikipedia-Article: Command–query separation, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Command%E2%80%93query_separation, Last Access: 21st November 2024.

-

Wikipedia-Article: Command-Query-Responsibility-Segregation, URL: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Command-Query-Responsibility-Segregation, Last Access: 21st November 2024.