This blog post offers a detailed explanation of the liskov substitution principle and gives an overview of the rules you should follow as a software engineer when dealing with inheritance in object-oriented programming to produce clean code. The following is a summary of some sources I have read however also includes my own opinion and knowledge on that topic. Code examples are written in Java.

Overview Link to heading

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) was first introduced by Barbara Liskov in 1987 in her article “Data Abstraction and Hierarchy” and is one of the five SOLID design principles of object-oriented programming.

Barbara Liskov (Source: Wikipedia).

The original definition of this principle is as follows:

If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2, then S is a subtype of T.

Ok, that sounds pretty complicated. So what does that even mean?

The LSP states that a program using objects of a base class T should be able to work correctly with objects of its derived class S without altering the program. In other words, all subclasses must behave in the same way as the base class.

Simply put:

If S is a Subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced by objects of type S.

Wherever you are using the base type, you should be able to use the subtype instead without causing any unwanted behavior in the program. That means: “Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types.”

Let’s take a closer look at that concept with an example:

Assume that class S inherits from class T.

Class S inherits from class T.

And then, let’s imagine that we have written a program where we have used class T in multiple places in the code and created instances of it T t = new T(). Now, we need to ensure that we can replace instances of class T with instances of class S at all these points without changing the program’s behavior.

So instead of

T t = new T()

you should be able to use

T t = new S()

and then the program should behave exactly the same way as before.

If this is the case, then the LSP holds. S was substituted for T!

Animals, Cats, Dogs and Tables Link to heading

Let’s take a step back and address a more fundamental question:

How should you actually use inheritance in programming?

Consider a classic example where the subclass Cat extends the base class Animal.

Class Cat inherits from class Animal.

If the Animal can do certain things, then the Cat must also be able to do all these things. All subclasses of Animal must be able to do these things.

But the subclasses may also be able to do more things than the base class. And by more things, I mean more specific things. The Cat class may contain the meow() method. But the Animal class does not contain the meow() method because it is a specific behavior of a cat. But that’s not a problem, because the Cat class can still be used instead of the Animal class without changing the behavior of the program. Because a cat can do everything that an animal can do in exactly the same way. So the LSP holds.

- This means: a Cat is a subset of an Animal.

- This means: a Cat IS an Animal.

- This means: an Animal is not necessarily a Cat. An Animal can also be a dog, for example.

This is why we speak of an is-a relation in programming when we talk about inheritance.

For example: a table is not an animal and therefore does not inherit from animal and therefore is not a subset of Animal.

Cat is a subset of Animal because it can do everything an animal can do (and more). Table is not a subset of Animal.

LSP Definition Link to heading

Let’s take a closer look at the original definition from Barbara Liskov (slightly simplified):

If for each object Os of type S there is an object Ot of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when Os is substituted for Ot, then S is a subtype of T.

The following diagram tries to explain this definition in a visual way:

LSP definition explained as a diagram.

- Os is an instance of class S.

- Ot is an instance of class T.

- The program P uses Ot.

- The program P’ uses Os.

If you use Os instead of Ot in Program P, and the behaviour of Program P is unchanged, then the LSP holds.

That means P’ must behave exactly like P.

Practical Example: Violated LSP Link to heading

When is the LSP actually violated?

If you are inheriting from the base class without making the subclass substitutable for the base class, then you are breaking the LSP.

In the following, a classic example of a program with violated LSP is shown. Consider we have a class Rectangle and a class Square where Square extends Rectangle.

Class Square inherits from class Rectangle.

In this example, square is not a proper subtype of rectangle, because the height and width of the rectangle are independently mutable. In contrast, the height and width of the square must change together. Since the user believes it is communicating with a rectangle, it could easily get confused.

Rectangle r = _________

r.setHeight(5);

r.setWidth(2);

assert(r.area() == 10)

If the blank line above produced a square, then the assertion would fail.

However let’s take a deeper look into the java code of this example. A rectangle can set its width and height independently. In contrast, whenever the width/height of a square is set, the height/width is changed accordingly. the setWidth() and setHeight() functions are inappropriate for a Square, since the width and height of a square are identical. So we notice that something goes wrong here. However let’s ignore this indication that there is a problem and sidestep this problem by overriding the setWidth and setHeight methods.

class Rectangle{

int width;

int height;

setHeight(height){

this.height = height;

}

setWidth(width){

this.width = width;

}

area(){

return width * height;

}

}

class Square extends Rectangle{

@Override

setHeight(height){

this.height = height;

this.width = height;

}

@Override

setWidth(width){

this.width = width;

this.height = width;

}

}

When using the code now, there is unexpected behaviour when using the square instead of the rectangle. Hence, the LSP breaks! Note: You should never receive anything unexpected from a subclass.

Rectangle r = new Rectangle()

r.setHeight(5);

r.setWidth(2);

System.out.println(r.area()); // 10

Rectangle r = new Square()

r.setHeight(5);

r.setWidth(2);

System.out.println(r.area()); // 4

A solution to this problem could be introducing a Shape class, where Rectangle and square are inheriting from:

Square and Rectangle both inherit from Shape.

Or an even better solution: use composition instead of inheritance.

Method Overriding Link to heading

The previous example showed a violation of the LSP. The LSP was violated because the methods setWidth() and setHeight() were overridden in the subclass. As the two methods in the subclass behaved differently, Square could no longer be used instead of Rectangle without changing the behaviour of the program. You may be asking yourself:

Does that mean method overriding is always a violation of Liskov Substitution Principle?

-> Answer: “it depends!”

The biggest problem with method overriding is that some specific method implementations in the derived classes might not fully adhere to the LSP and therefore fail to preserve type substitutability. Of course, it’s valid to make an overridden method to accept arguments of different types and return a different type as well, but with full adherence to the following five rules:

1. If a method in the base class takes argument(s) of a given type, the overridden method should take the same type or a supertype (A.K.A. contravariant method arguments).

2. If a method in the base class returns void, the overridden method should return void as well.

3. If a method in the base class returns a primitive, the overridden method should return the same primitive.

4. If a method in the base class returns a certain type, the overridden method should return the same type or a subtype (A.K.A. covariant return type).

5. If a method in the base class throws an exception, the overridden method must throw the same exception or a subtype of the base class exception.

Design by Contract (Preconditions, Postconditions, Invariants) Link to heading

It is well known that “contracts” are an important concept in software development. Modules must be able to rely on each other by adhering to “rules” that have been agreed on in advance. Design by Contract (DbC) is an approach to design software in this way. The aim is to ensure the smooth interaction of individual program modules by defining formal contracts.

DbC was developed and introduced by Bertrand Meyer with the development of the programming language Eiffel.

Bertrand Meyer (Source: Wikipedia).

The idea of DbC is to define as precisely as possible what a software module should do.

The credo: “If we don’t state what a module should do, there is little likelihood that it will do it.”

One of the main goals of DbC is increasing software quality (reliability). The smooth interaction between program modules is achieved through a contract that must be adhered to when using a method, for example. This contract consists of preconditions, postconditions and class invariants.

Preconditions Link to heading

Preconditions are assurances that the caller must adhere to.

Preconditions determine under what circumstances a method should be callable.

Preconditions are requirements that must be met before calling a method. These conditions describe the expected state of the system or input before the method is executed. If the preconditions are not met, the method may either throw an exception or handle the error in another way.

The following Code example shows a method with the defined Precondition: 0 < num <= 5.

public class Foo {

public void doStuff(int num) {

// precondition: 0 < num <= 5

if (num <= 0 || num > 5) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Invalid Precondition: Input out of range 1 – 5"

);

}

// perform some operations here…

}

}

In this example, the precondition for the doStuff method states that the num parameter value must be in the range 1 to 5. This precondition is enforced with a range check inside the method. If the precondition is not met, an IllegalArgumentException is thrown.

When the precondition is not met (i.e. its evaluation results in false), then the code that is calling the method is wrong. The caller has to ensure that the precondition is met beforehand.

Postconditions Link to heading

Postconditions are assurances that the callee will uphold.

Postconditions specify the conditions that must be met after the completion of the method call.

Postconditions are requirements that should apply after the execution of a method. These conditions describe the expected state of the system or return values after the method has been successfully completed.

The following Code example shows a method with the defined Postcondition: newNum > num.

public class Foo {

public int doStuff(int num) {

// perform operation

int newNum = num + 1;

// postcondition: newNum must be greater than num

if (newNum <= num) {

throw new IllegalStateException(

"Invalid Postcondition: newNum must be greater than num"

);

}

return newNum;

}

}

In this example, the postcondition for the doStuff method states that the newNum value must be bigger than the num value at the end of the method execution. This postcondition is enforced with a check after the performed operation and before the value gets returned. If the postcondition is not met, an IllegalState exception is thrown. If a postcondition is not fulfilled, there is an error in the subroutine itself (i.e. in the operations within the method): The subroutine should have ensured that the postcondition is fulfilled.

To sum up, preconditions and postconditions form a kind of contract: If the calling code fulfills the precondition, then the subroutine is obliged to fulfill the postcondition.

Class Invariants Link to heading

Invariants are immutable basic assumptions that apply across all instances of a class. Invariants ensure, that certain conditions (or states) are met at entry and exit point of methods. Therefore, Invariants are a combination of pre- and postconditions together. In Java, invariants refer to conditions or properties that should remain unchanged throughout the entire life cycle of an object. Invariants play an important role in ensuring the consistency and validity of objects. A class invariant is an assertion concerning object properties that must be true for all valid states of the object.

The following Code example shows a method with the defined Invariant: num < limit.

public class Foo {

// invariant: num < limit (should apply in every state)

private int limit;

public void doStuff(int num) {

//precondition: num < limit

if (num >= limit) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Invalid Precondition: num must be below limit"

);

}

// perform operation

int newNum = num + 1;

// postcondition: num < limit

if (num >= limit) {

throw new IllegalStateException(

"Invalid Postcondition: num must be below limit"

);

}

return newNum;

}

}

The Foo class specifies a class invariant that num must always be below the limit. This rule should apply for every state in which the program may be. In the code example the invariant is enforced with a check before and after the performed operation. If the invariant is violated, an exception is thrown.

As illustrated in the previous three code examples, preconditions, postconditions and invariants are usually formulated as Boolean expressions.

- Precondition: Is checked before the method is executed.

- Postcondition: Is checked after the method is executed.

- Invariant: Is checked before and after the execution of the method.

If every code adheres to the contract, no errors can occur and the method is guaranteed not to deliver unexpected results. The use of DbC creates a chain of contracts that ultimately ensures more robust software. If every single element in the chain can guarantee to fulfill the postcondition when the precondition has been met beforehand, fewer errors occur due to incorrect assumptions of developers.

But what does this have to do with the LSP?

-> By defining class invariants, preconditions and postconditions, a module can be replaced by any other module if it fulfills the same “contract”. And that is exactly what the LSP is all about.

Three rules to create well-behaved subtypes Link to heading

In their book “Program Development in Java: Abstraction, Specification, and Object-Oriented Design”, Barbara Liskov and John Guttag formulated three rules to create subtypes that adhere to the LSP – the signature rule, the properties rule, and the methods rule.

The methods rule Link to heading

Definition:

Calls of subtype methods must “behave like” calls to the corresponding supertype methods. A subtype method can weaken the precondition and can strengthen the postcondition. Both conditions must be satisfied to achieve compatibility between the sub- and supertype methods.

Weaken the precondition by example Link to heading

A subtype can weaken (but not strengthen) the precondition for a method it overrides. When a subtype weakens the precondition, it relaxes the constraints imposed by the supertype method.

Example: the doStuff() method in the Foo class defines that the method input num must have a value in between 0 and 6 (0 < num <= 5).

public class Foo {

public void doStuff(int num) {

// precondition: 0 < num <= 5

// perform some operations here…

}

}

Let’s now override the doStuff method with a weakened precondition:

public class Bar extends Foo {

@Override

public void doStuff(int num) {

// precondition: 0 < num <= 10

// perform some operations here…

}

}

Here, the precondition is weakened in the overridden doStuff method to 0 < num <= 10, allowing a wider range of values for num. All values of num that are valid for Foo.doStuff are valid for Bar.doStuff as well. Consequently, a client of Foo.doStuff doesn’t notice a difference when it replaces Foo with Bar. Conversely, when a subtype strengthens the precondition (e.g. 0 < num <= 3 in our example), it applies more stringent restrictions than the supertype (and this is not allowed). For example, values 4 & 5 for num are valid for Foo.doStuff, but are no longer valid for Bar.doStuff. This would break the client code that does not expect this new tighter constraint.

Strengthen the postcondition by example Link to heading

The subtype can strengthen (but not weaken) the postcondition for a method it overrides. When a subtype strengthens the postcondition, it provides more than the supertype method.

Example: the doStuff() method in the Foo class defines the postcondition newNum > num.

public class Foo {

public int doStuff(int num) {

// perform operation

// postcondition: newNum > num

}

}

Let’s now override the doStuff() method with a strengthened postcondition:

public class Bar extends Foo{

// Some properties and other methods...

@Override

public int doStuff(int num) {

// perform operation

// postcondition 1: newNum > num

// postcondition 2: newColor.equals(“blue”)

}

}

The overridden doStuff method in Bar strengthens the postcondition by additionally ensuring that after the performed operations the newColor equals to “blue” as well. Consequently, any client code relying on the postcondition of the doStuff() method in the Foo class notices no difference when it substitutes Bar for Foo. Because postcondition 1 is met as well in the subclass.

Conversely, if Bar were to weaken the postcondition of the overridden doStuff() method (which is not allowed), it would no longer guarantee that newNum > num. This might break client code given a Bar as a substitute for Foo.

The properties rule Link to heading

Definition:

“The subtype must preserve all properties that can be proved about supertype objects.” This rule states that all subtype methods (inherited and new) must maintain or strengthen the supertype’s class invariants.

Example: the Foo class defines a class invariant num < upperLimit.

public class Foo {

// invariant: num < upperLimit (should apply in every state)

private int upperLimit;

public void doStuff(int num) {

// perform some operations

}

}

Let’s now override the doStuff() method with a maintained/strengthened invariant:

public class Bar extends Foo{

private int lowerLimit;

@Override

public void doStuff(int num) {

// this method content has to maintain or strengthen the supertype’s class invariants

// Maintain-Example: ensuring that num < upperLimit

// Strengthen-Example: ensuring that (num < upperLimit) && (num > lowerLimit)

}

}

In this example, the class invariant in Foo is preserved/strengthened by the overridden doStuff method in Bar. Conversely, if the class invariant is not preserved by the subtype (which is not allowed), it breaks any client code that relies on the supertype.

The History Constraint Link to heading

The history constraint states that the subclass methods (inherited or new) shouldn’t allow state changes that the base class didn’t allow. History constraints describe the “historical evolution” (=the state changes).

public abstract class Car {

// mileage allowed to be set once at the time of creation.

// mileage value can only increment thereafter.

// mileage value cannot be reset.

protected int mileage;

public Car(int mileage) {

this.mileage = mileage;

}

// Other properties and methods...

}

The Car class specifies a constraint on the mileage property. The mileage property can be set only once at the time of creation and cannot be reset thereafter.

Let’s now define a ToyCar that extends Car:

public class ToyCar extends Car {

public void reset() {

mileage = 0;

}

// Other properties and methods

}

The ToyCar has an extra method reset that resets the mileage property. In doing so, the ToyCar ignored the constraint imposed by its parent on the mileage property. This breaks any client code that relies on the constraint. So, ToyCar is not substitutable for Car.

The Signature Rule Link to heading

Definition:

“The subtype objects must have all the methods of the supertype, and the signatures of the subtype methods must be compatible with the signatures of the corresponding supertype methods.”

To recap: The signature of a method is defined by:

- its name

- the number of parameters

- the type of parameters

- the sequence/order of parameters

Method argument types Link to heading

The rule states that the overridden subtype method argument types can be identical or wider than the supertype method argument types. Java’s method overriding rules support this rule by enforcing that the overridden method argument types match exactly with the supertype method.

- If a method in the base class takes argument(s) of a given type, the overridden method should take the same type or a supertype (= contravariant method arguments).

Return types Link to heading

The return type of the subtype method can be narrower than the return type of the supertype method. This is called covariance of the return types. Covariance indicates when a subtype is accepted in place of a supertype. Java supports the covariance of return types. Let’s look at an example:

public abstract class Foo {

public abstract Number generateNumber();

// Other Methods

}

The generateNumber() method in Foo has defined the return type as Number. Let’s now override this method by returning a narrower type of e.g. Integer:

public class Bar extends Foo {

@Override

public Integer generateNumber() {

return new Integer(10);

}

// Other Methods

}

Because Integer IS-A Number, a client code that expects Number can replace Foo with Bar without any problems.

On the other hand, if the overridden method in Bar were to return a wider type than Number, e.g. Object, that might include any subtype of Object e.g. a Truck. Any client code that relied on the return type of Number could not handle a Truck!

Fortunately, Java’s method overriding rules prevent an overridden method returning a wider type.

- If a method in the base class returns void, the overridden method should return void

- If a method in the base class returns a primitive, the overridden method should return the same primitive

- If a method in the base class returns a certain type, the overridden method should return the same type or a subtype (= covariant return type)

Exceptions Link to heading

The subtype method can throw fewer or narrower (but not any additional or broader) exceptions than the supertype method. This is understandable because when the client code substitutes a subtype, it can handle, the method throwing fewer exceptions than the supertype method. However, if the subtype’s method throws new or broader checked exceptions, it would break the client code. Java’s method overriding rules already enforce this rule for checked exceptions. However, overriding methods in Java CAN THROW any RuntimeException regardless of whether the overridden method declares the exception.

- If a method in the base class throws an exception, the overridden method must throw the same exception or a subtype of the base class exception.

Summary of rules: Link to heading

-

Preconditions cannot be strengthened in a subtype.

-

Postconditions cannot be weakened in a subtype.

-

Invariants of the supertype must be preserved (or strengthened) in a subtype.

-

History constraint: subclass methods shouldn’t allow state changes that the base class didn’t allow.

-

Subtype method argument types can be identical or wider than the supertype method argument types(= contravariant method arguments)

-

The return type of the subtype method can be narrower than the return type of the supertype method

-

If a method in the base class returns void, the overridden method should return void as well

-

If a method in the base class returns a primitive, the overridden method should return the same primitive

-

If a method in the base class returns a certain type, the overridden method should return the same type or a subtype (= covariant return type)

This is a lot to think about. How are you supposed to remember all this and apply it in your daily life as a software developer? In my opinion, there are two options:

-

You use inheritance in your code. However then you have to apply all these rules and think about all the mentioned stuff. If you don’t, then your code is bad and breaks the LSP!

-

Don’t use inheritance at all! Use composition instead! In this case you don’t have to think about all the mentioned stuff. And your code is clean as well!

I would go with option 2! 😉

Why is LSP so important? Link to heading

I think LSP is so important because it ensures that no unexpected behaviour happens in the program. Therefore it is easier to maintain and easier to debug.

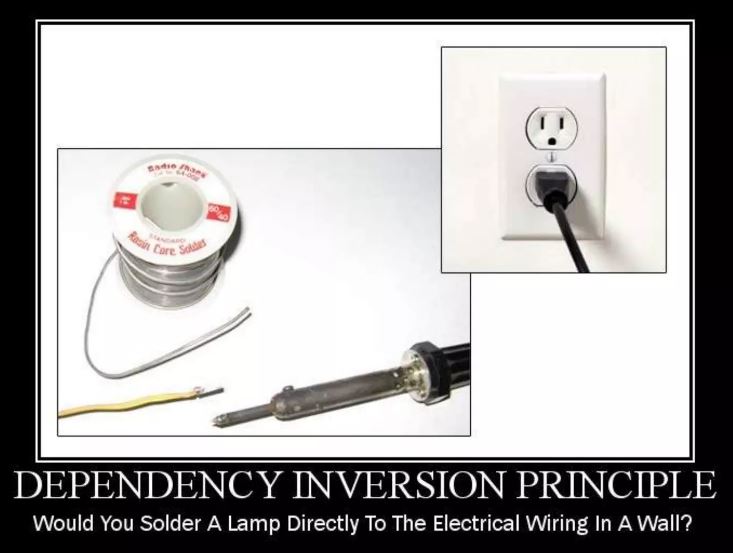

Furthermore by following the LSP you can ensure that the building blocks of your application are more flexible and can be swapped out easily without having to fear that something breaks. For instance a Cat can be used instead of an Animal without any problems. We all know that changing and swapping things out are important things in software development. That’s what also the “Dependency Inversion Principle” teaches us. Would you solder a lamp directly to the electrical wiring in a wall? Or would you use a plug instead?

Dependency Inversion Principle (Source: Stack Overflow).

Behavioral consistency:

The LSP ensures that an object of a derived type behaves exactly like an object of the base type. This allows objects to be exchanged arbitrarily without changing the program’s behavior. This is important for the consistency and predictability of the code.

Interoperability and Extensibility:

By following the LSP, different classes that implement the same base type can seamlessly interact with each other. This facilitates the integration of new classes into existing systems without requiring changes to existing code (See: Open Closed Principle).

Documentation and Understandability:

The LSP contributes to better code understandability. When developers know that they can exchange objects without causing unexpected side effects, the code becomes more transparent and easier to understand.

Testability:

Classes that adhere to the LSP are generally more testable. Tests written for the base type can also be used for derived types without requiring specific adjustments.

Conclusion Link to heading

I don’t think LSP is difficult to understand. However I think it is difficult to actually follow it. Most of the time subclassing is done wrong. Most of the time subclassing is used too much or it is used in situations where it should not be used. Inheritance should not be overused!

A fundamental Rule in OOP states: “Favor composition over inheritance!”

So maybe in the next situation where you think about using inheritance to solve a problem, you should ask yourself the question: “How could I solve the problem by using composition?”. I would argue that most of the time composition would lead to a better solution than inheritance.

I would even go one step further: Ideally, inheritance should not be used anywhere in your code. Now you might be wondering: what was the point of this article then if inheritance shouldn’t be used anyway? Well, unfortunately, inheritance is still used very often. In Java, for example, it is a fundamental concept on which the entire language is built on.

While programming you should ask yourself the questions:

- Could the problem be solved better by using composition?

- Is my subclass substitutable for the base class without breaking the program?

- Is my subclass in an “is-a” relationship to the base class? Is my cat an animal? is my dog an animal? is my table an animal?

- What are my preconditions, postconditions and invariants?

- Do I break the signature-, properties- or method rule?

Reference Link to heading

Books Link to heading

-

Barbara Liskov and John Guttag: Program Development in Java: Abstraction, Specification, and Object-Oriented Design., Publisher: Addison-Wesley, Year: 2000, ISBN: 0201657686

-

Robert C. Martin: Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design (Robert C. Martin Series), Publisher: Pearson, Year: 2017, ISBN: 0134494164

Academic publications Link to heading

-

Matthias Hausherr: Design By Contract in Java - Seminarbericht WS06/07, Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz (Hochschule für Technik – Studiengang Informatik), Betreuender Dozent: Prof. Dr. Dominik Gruntz, Veröffentlicht: Windisch, 15. November 2006, URL: https://silo.tips/download/design-by-contract-in-java, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Franz Puntigam: TU Wien:Fortgeschrittene objektorientierte Programmierung VU (Puntigam)/Mitschrift SS17, Year: 2017, URL: https://vowi.fsinf.at/wiki/TU_Wien:Fortgeschrittene_objektorientierte_Programmierung_VU_(Puntigam)/Mitschrift_SS17, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

Websites Link to heading

-

Wikipedia-Article: Design by Contract, URL: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Design_by_Contract, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Wikipedia-Article: Covariance and contravariance (computer science), URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Covariance_and_contravariance_(computer_science), Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Baeldung-Article: Liskov Substitution Principle in Java, URL: https://www.baeldung.com/java-liskov-substitution-principle, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Baeldung-Article: Method Overloading and Overriding in Java, URL: https://www.baeldung.com/java-method-overload-override, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

Videos Link to heading

-

Video from Christopher Okhravi: Liskov’s Substitution Principle | SOLID Design Principles (ep 1 part 1), URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ObHQHszbIcE, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Video from Web Dev Simplified: Liskov Substitution Principle Explained - SOLID Design Principles, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJQMqNOC4Pc&t=176s, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Video from Christopher Okhravi: Liskov Substitution Principle (SOLID), The Robustness Principle, and DbC | Code Walks 018, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bVwZquRH1Vk&t=144s, Last Access: 13th September 2024.