This blog post offers an explanation of Strategy Design Pattern by Gang of Four. The examples are written in Java.

A duck can fly and quack (and can do probably much more things). Image-Source: Pixabay

The Problem that the strategy pattern solves Link to heading

Let’s say we have a Duck class. And then we have a CityDuck (living in the city) and a WildDuck (living in the forest). We use inheritance – so CityDuck and WildDuck inherit from Duck. The subclasses are responsible for implementing their own version of the display() method. Wild-ducks can display themselves differently than city-ducks for instance. So they have to override the display() method. But the quack() method is shared amongst all these subclasses. Inheritance is used here for code reuse.

CityDuck and WildDuck inherit from Duck

What is the problem here? The problem is CHANGE (which happens everytime). The only constant in software development is change! When requirements change, our current software design may not necessarily be appropriate for the incoming requirements. An example for such a change could be the following:

What if we have another method, for example fly()? Because ducks can fly. We add the method to the base class Duck. But then you want to introduce a new class called RubberDuck which inherits from Duck. RubberDuck has its own display() method. But rubber-ducks can’t fly. Now we have a problem! rubber-ducks can’t fly however they inherit the fly() method from their parent class Duck -> which is wrong! ⚠️

RubberDuck inherits the fly() method! Now everyone who is using a RubberDuck object can call the fly() method on it which should not be possible because rubber-ducks can’t fly.⚠️

And what if we wanna add a new class called MountainDuck (which lives in the mountains). This duck implements its own display() method. But it implements also its own fly() method because the duck has a specific way to fly (ultrafast for instance).

And then we add a new class called CloudDuck. This duck also overrides display() and fly() methods. But the cloud-duck flys EXACTLY the same as the mountain-duck. What are we doing now? We cannot reuse the same code from the mountain-duck. So we have to copy and paste. And that is very, very bad! ⚠️ (cf. DRY Principle)

Some might say you could solve some of these problems with “more inheritance”. You could for instance introduce a new base class just for MountainDuck and CloudDuck where the both ducks are inheriting from. But the more classes you create and inherit from, the more “inflexible” all of that gets.

The problem is, that you can’t share behaviour over classes that are in the same hierarchy (horizontally). Inheritance only works by sharing code from top to bottom.

When it comes to inheritance, code cannot be shared between classes which are in the same hierarchy.

The solution to problems with inheritance is not “more inheritance”. The solution is composition! And that’s exactly what the strategy pattern does.

Overview Link to heading

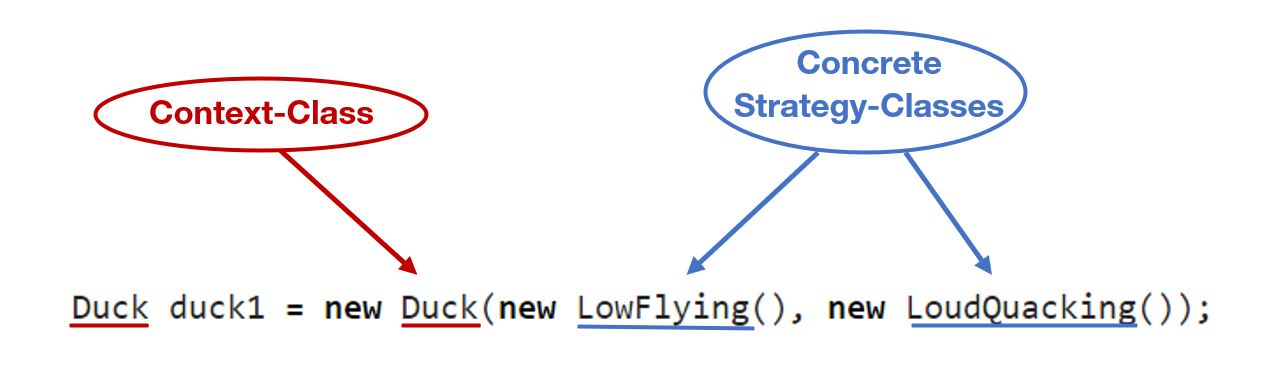

Why is the Strategy Pattern so useful? Because of its flexibility! In this pattern, behaviors are extracted from a class (called Context) into other classes (called Concrete Strategies) and loosely coupled to the class (Context) via interfaces. The context class then simply calls the code of the concrete strategies. This allows objects and their behaviors to be composed easily. Here’s an example of how a client might use the Strategy Pattern:

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Duck duck1 = new Duck(new LowFlying(), new LoudQuacking());

duck1.fly(); // prints "Low Flying"

duck1.quack(); // prints "Loud Quacking"

Duck duck2 = new Duck(new HighFlying(), new QuietQuacking());

duck2.fly(); // prints "High Flying"

duck2.quack(); // prints "Quiet Quacking"

}

The behaviors are passed to the ducks via dependency injection.

Objekte werden mit Verhaltensweisen zusammengebaut (lose gekoppelt).

The Strategy Pattern is a prime example that composition is better than inheritance. We need Inheritance much much less than we believe.

The concrete implementations (LoudQuacking, QuietQuacking, etc.) can vary just as much as they want – without having to change the code of the context class (Duck). And that is the power of the strategy pattern!

The Pattern itself Link to heading

This is how the full pattern looks like in UML (Unified Modeling Language):

UML Diagram of the Strategy Pattern.

The Context class holds one or more objects of type Strategy as member variable. The member methods of the Context class then simply call the behaviour() methods implemented in the ConcreteStrategy classes.

In the following, the full duck example is displayed in UML. In contrast to the UML above, the duck example shows how the pattern works with multiple Strategies (IFlyBehaviour and IQuackBehaviour):

One example of the strategy pattern in action.

Intent of the strategy pattern Link to heading

The original GoF Design-Pattern Book states the intent of the strategy pattern as follows:

“Define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.”

In the following, I will try to explain each phrase of the intent individually. Note! In this original intent the term “family of algorithms” means the same as “strategy”. In the following, the word strategy is mainly used instead of “family of algorithms”.

“Family of algorithms”:

In this example, the classes IFlyBehavior and IQuackBehavior can be seen as ‘families’.

“Algorithms”:

Algorithms are the behaviors (i.e., concrete implementations of the Strategy). These are LowFlying, HighFlying, LoudQuacking, and QuietQuacking. LowFlying and HighFlying belong to the IFlyBehavior family. LoudQuacking and QuietQuacking belong to the IQuackBehavior family.

“Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it”:

Each “Concrete Strategy Class” has its own independent behavior. These concrete implementations of the IFlyBehavior and IQuackBehavior families can be completely different from one another.

“make them interchangeable”:

Concrete behaviors can be easily swapped out (as long as they implement the same interface). For example, you can introduce a new class FastFlying that implements IFlyBehavior. Then, you can simply assign the behavior new FastFlying() to duck1 instead of the behaviour new LowFlying(). Here, the algorithm gets decoupled from the one that is using the algorithm. Whoever is using the algorithm is not forced to change when one of the algorithms is changed.

When should you use this pattern? Link to heading

-

Use the Strategy pattern when you want to use different variants of an algorithm within an object and be able to switch from one algorithm to another during runtime.

-

Use the Strategy when you have a lot of similar classes that only differ in the way they execute some behavior.

-

Use the pattern to isolate the business logic of a class from the implementation details of algorithms that may not be as important in the context of that logic.

-

Use the pattern when your class has a massive conditional statement that switches between different variants of the same algorithm.

Reference Link to heading

Books Link to heading

-

Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson and John Vlissides: Design Patterns – Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, Publisher: Addison-Wesley, Year: 1995, ISBN: 0201633612

-

Eric Freeman, Elisabeth Robson, Kathy Sierra and Bert Bates: Head First Design Patterns: Building Extensible and Maintainable Object-Oriented Software 2nd Edition, Publisher: O’REILLY, Year: 2021, ISBN: 9781492078005

Videos Link to heading

- Video from Christopher Okhravi: Strategy Pattern – Design Patterns (ep 1), URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9ejT8FO-7I, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

Websites Link to heading

-

Refactoring Guru Website: Strategy, URL: https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/strategy, Last Access: 13th September 2024.

-

Refactoring Guru Website: Strategy in Java, URL: https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/strategy/java/example, Last Access: 13th September 2024.